I’m sitting at my desk, trying to write, and my inner Critic has already pulled up a chair.

It doesn’t yell. It’s quiet. Primitive. From part of the brain that evolved to keep me from embarrassing myself in front of the tribe (or the internet).

It isn’t malicious. It acts in good faith. It genuinely believes it’s helping. It wants to keep the words clean and sharp.

The problem isn’t what this voice does.

It’s when it shows up.

Productivity doesn’t mean writing better.

It means writing in the correct mode at the correct time.

When I’m drafting, the Critic wants to polish the work in real time. It wants to protect the outcome before there’s anything even worth protecting.

That impulse makes sense, just not at the beginning.

Judgment doesn’t refine fresh ideas. It interferes with them

You can’t listen to the devil on one shoulder that critiques you, whilst also trying to hear the voice that nudges you toward a “flow state.” Those two signals cancel each other out.

Flow depends on permission. So, if any judgment happens uninvited, that permission is revoked.

Two tasks that cannot coexist

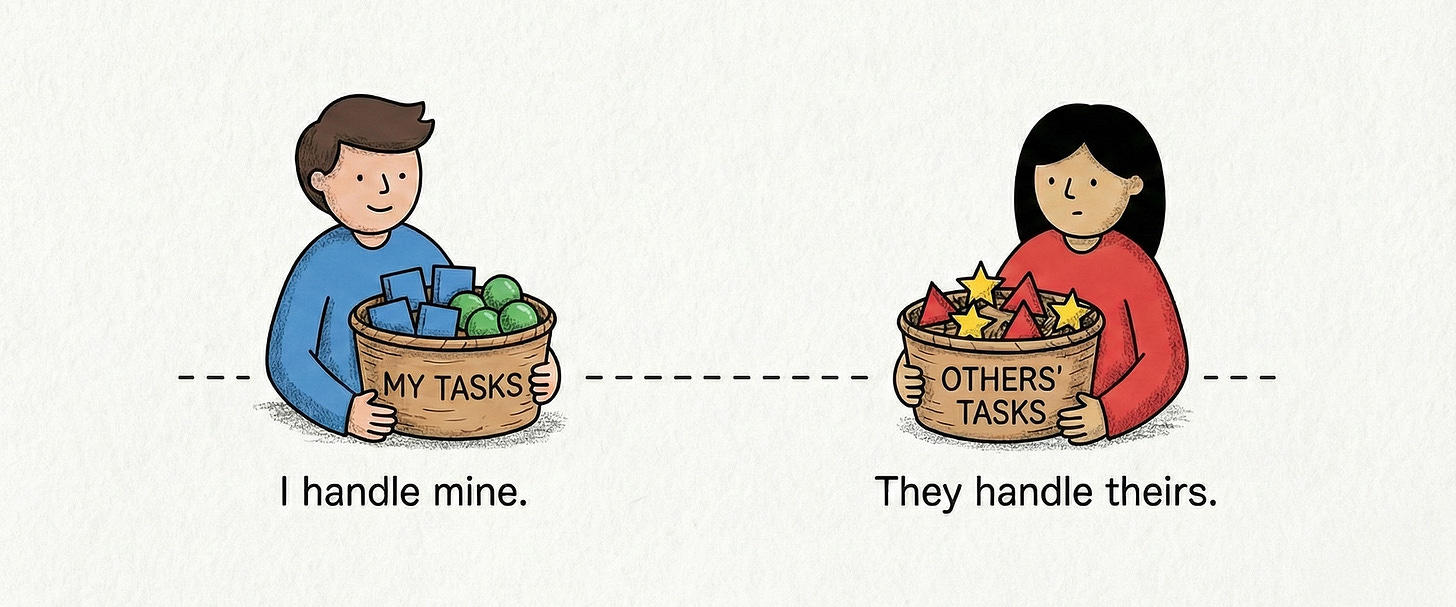

The idea that made this click for me came from Alfred Adler’s concept of the Separation of Tasks.

Adler, a 20th-century psychologist, argued that most human conflict comes from people meddling in tasks that are not their own.

If we don’t clearly separate our tasks and trust others will do the same, more conflicts arise, and we’re less fulfilled.

I realised I was doing this internally.

I was allowing my Critic to interfere in the Creator’s task.

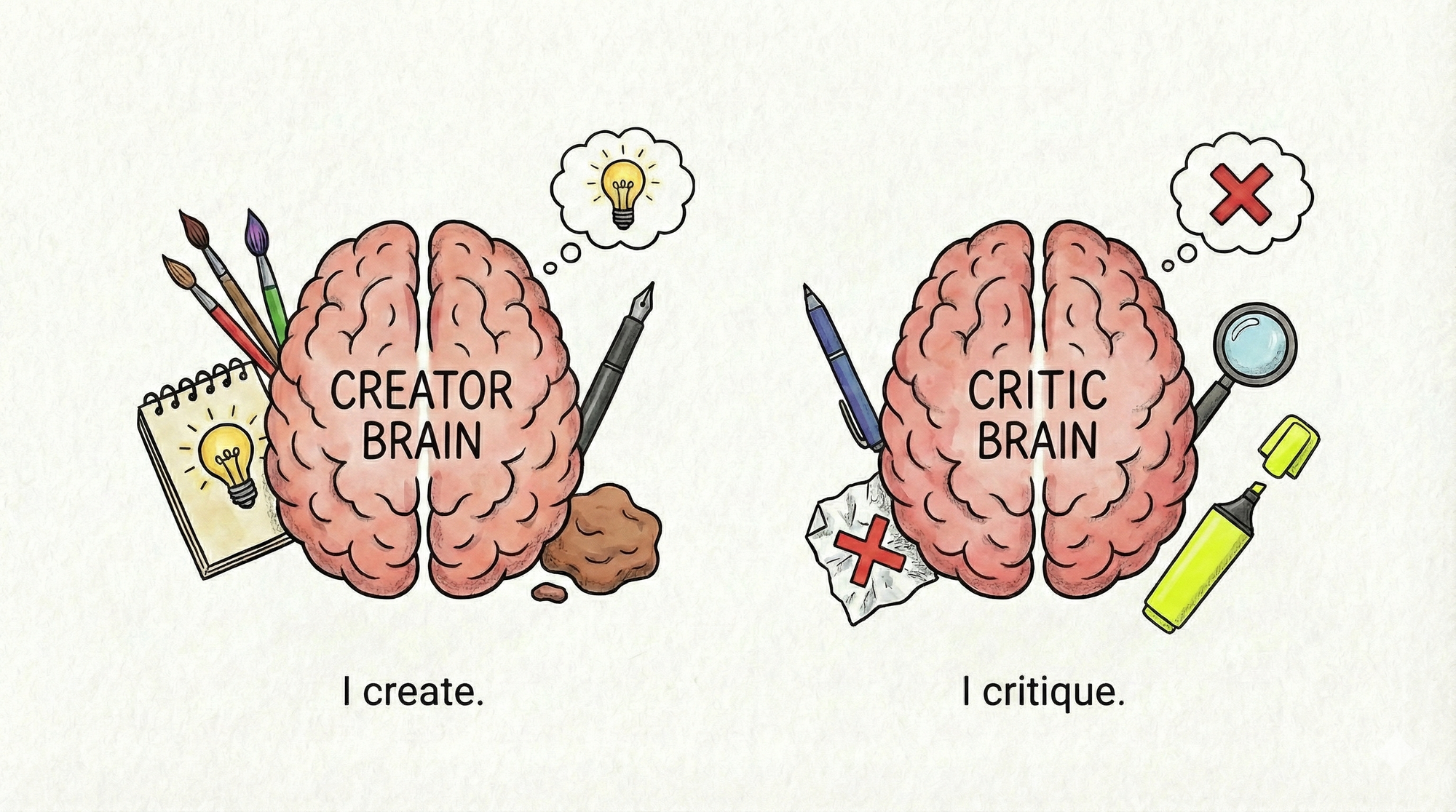

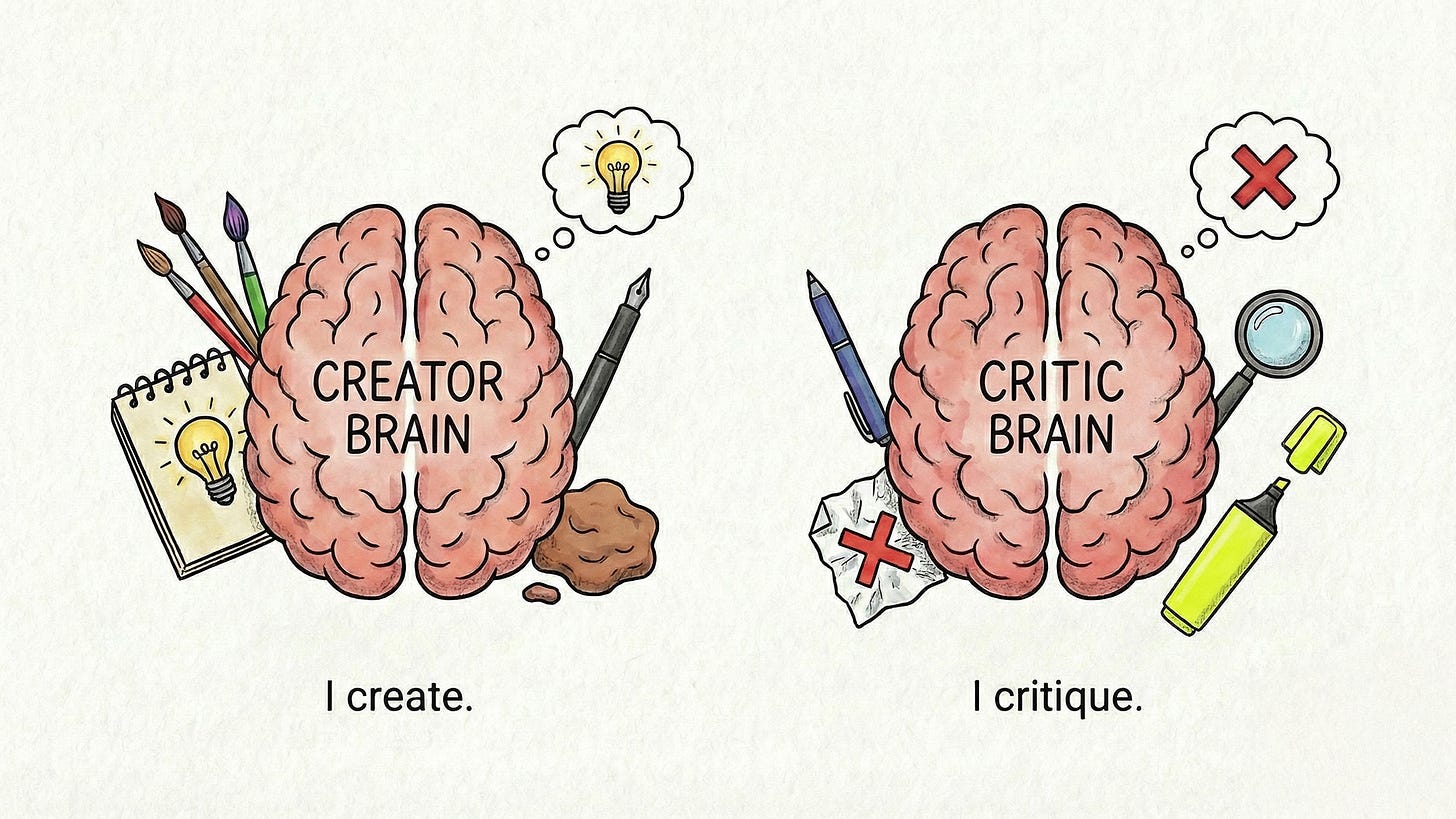

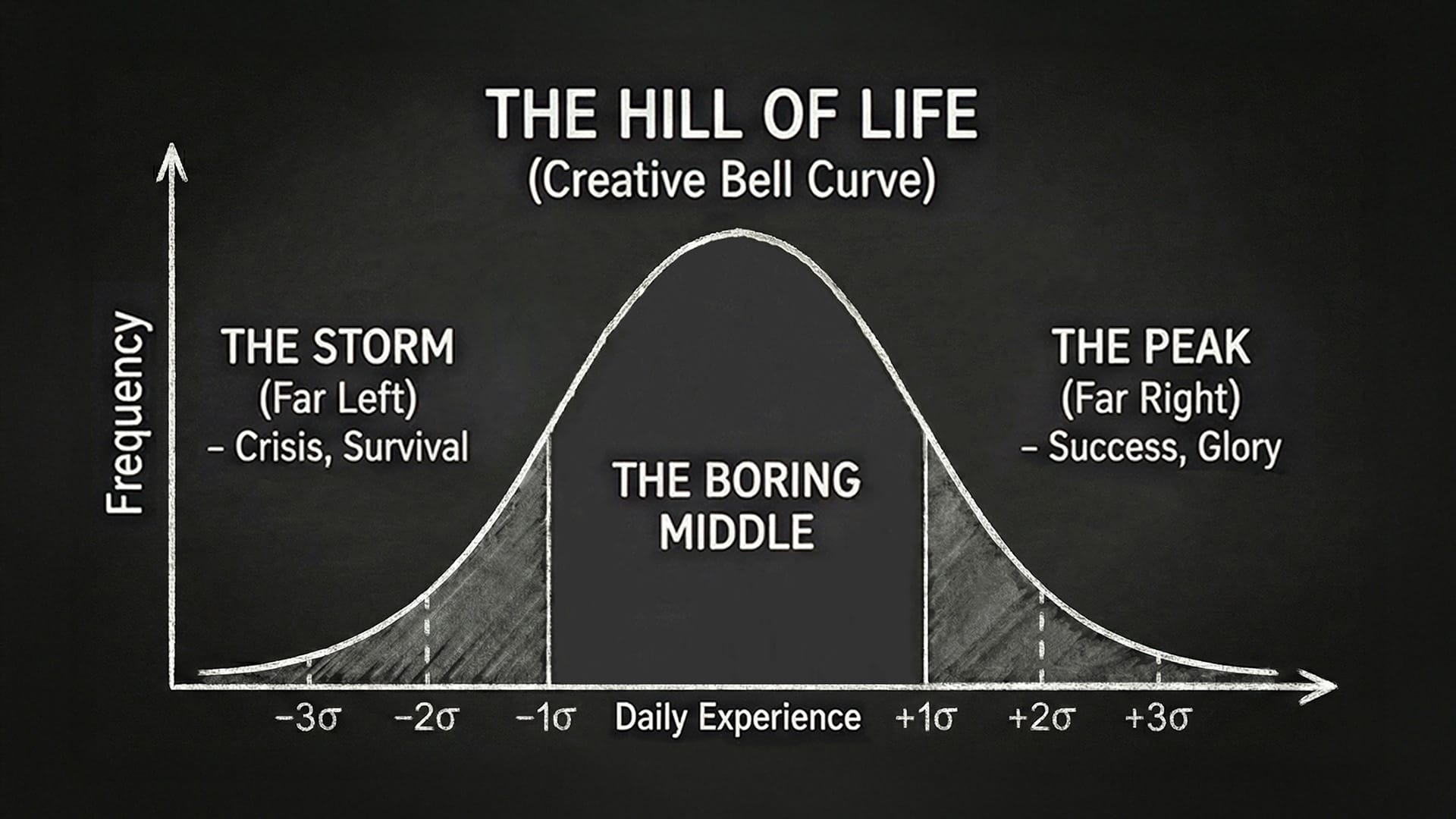

These roles require completely different energies:

- The Creator is expansive, messy, and fast. It generates raw material, not quality.

- The Critic is reductive, precise, and cold. It’s about improving what already exists.

Trying to contend with both at the same time is like editing a sentence that hasn’t been written yet.

Because if I edit while I write, something predictable happens.

I’ll start a sentence with a half-formed idea, and before it’s finished, the Critic interrupts:

That’s so obvious.

That’s not correct.

You can say this better.

So I stop. I swap out some words. I tighten up the phrasing. I try to polish off the sentence before the meaning has been captured.

A few minutes later, the sentence may look fine, but some of the heart behind the idea is gone.

This is the real cost of early judgment: reduced spontaneity.

The Critic doesn’t just slow the process. It nudges the writing towards what sounds safe instead of what feels true.

Every time I stop mid-thought to fix a sentence or sound more intelligent, the momentum stops, and I lose the thread or a potential breakthrough.

Spew first, judge later

There’s a video where Judd Apatow describes his writing process as two distinct phases:

- Spewing: getting the raw, unfiltered material out.

- Assessing: the cold, deliberate edit.

His point is simple: if you assess while you’re spewing, you kill all the fun before it has a chance to exist.

This is why the idea of the “shitty first draft” is mandatory.

As Anne Lamott puts it, the first draft gives you permission to be clumsy, repetitive, and wrong. Not because that’s the goal, but because it’s the only way anything real shows up.

A first draft is for excavation, not architecture.

Even though it may be poorly structured, you’ve still captured the chain of decisions and your thought process.

A perfect first paragraph, on the other hand, sets a trap. It raises the bar for everything that follows. Every new sentence gets compared, and by nature, perfectionism becomes a passenger.

A messy draft removes pressure, giving the work permission to be bad.

Write like no one’s reading

If I knew no one would ever read my first draft, I would write differently.

I’d be more direct. More opinionated. Less careful. I’d stop circling ideas and say the thing straight.

The irony is that this promise is always true. You control what gets shared. No one ever has to see the first draft—not a partner, not an agent, not an audience.

And yet we write as if the rough version itself is already under review.

That’s an ego problem, not a craft problem.

The ego wants to look competent at all times. It wants the first version to already signal talent, originality or intelligence. The Creator doesn’t care about any of that. It simply needs movement.

Only when the Creator has finished the “shitty first draft” can the Critic get involved.

Changing gears is always best done after a little distance. When I step away and come back later with fresh eyes, the judgment feels more accurate and less emotional.

Learning to adhere to the invisible lines that separate these two roles is an ongoing practice. I need to remind myself:

- The first pass is for volume, not quality.

- There will always be time to improve the work later.

- If the Critic shows up early, don’t argue and ignore it.

Sometimes I leave myself notes between sections. Sometimes I write badly on purpose. Sometimes I let entire paragraphs exist just to see if it leads anywhere interesting.

The point is: respect the right to have a messy start, free of critique.

Draft first. Edit later. Enforce the separation.

If you enjoyed this post, join The Creative Apprentice to get my weekly dispatches on mastery, craft, and the creative process delivered directly to your inbox.

Discussion